France conquered Vietnam in the second half of the 19th century CE, establishing the colony of Indochina, which spanned most of southeast Asia.

During World War II Japan took over.

After its defeat in that war the Vietnamese hoped to gain independence again, but the French re-established their former position.

The Viet Minh, a communist and nationalist movement, started the First Indochina War, a guerrilla campaign to oust the French.

Gradually it took control over large parts of the countryside, especially in the north.

The rugged terrain prevented the French from using mobile warfare and they lacked troops to establish a long line of static defenses.

Instead, the French general Henri Navarre developed the 'hedgehog' concept that came down to establishing forward bases behind enemy lines,

which were to be used as launchpads for offensives against the Viet Minh, or to lure the enemy into open battles.

This was successful at Na San, yet Dien Bien Phu proved much more difficult.

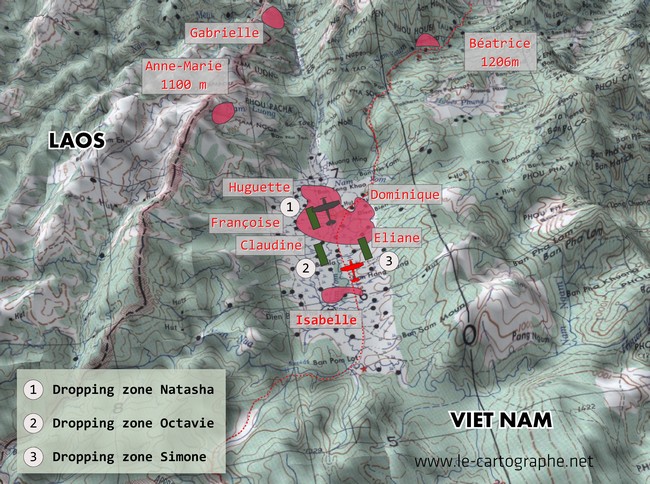

In November 1953 CE the French dropped 9,000 paratroops in three areas around Dien Bien Phu and swept some light resistance aside.

The town was an important center of rice and opium production for the Viet Minh and its capture disrupted their supply lines.

Because it was 350 kilometers from Hanoi, deep in enemy territory, the French could not supply it overland either and had to do so by air.

Because their number of troops was limited, the French took up position in the village and its valley and left the surrounding hills and mountains unoccupied, a grave mistake.

After establishing themselves, they started fortifying their positions, were reinforced to 16,000 men plus ten M24 light tanks.

The soldiers were a mix of regular troops, Foreign Legionnaires, Algerian and Moroccan tirailleurs and locally recruited milita.

At Na San, the Viet Minh general Vo Nguyen Giap had wasted the lives of many of his men in futile frontal assaults.

At Dien Bien Phu he did somewhat better.

He used the height advantage of the surrounding hills, stacked the area with four infantry divisions and one artillery division, almost 50,000 men.

Support troops numbering 55,000 constructed roads and carried, bicycled and trucked in enough supplies, heavy artillery and anti-air guns

to keep the five divisions fighting, which the French had deemed impossible.

Vo Nguyen Giap carefully scouted the French positions, while leaving the enemy in doubt about his own strength and locations.

At the end of January 1954 CE the Viet Minh closed the ring around Dien Bien Phu.

In mid-March they started to shell the French in earnest.

The Vietnamese largely avoided indirect artillery fire.

Instead, they used old-fashioned direct fire from well protected and camouflaged gun sites, which proved effective.

Their 200 guns and heavy mortars progressively destroyed the 60 French ones.

Follow-up assaults took the outer French positions "Beatrice" and "Gabrielle" within a day; counter-attacks failed.

"Anne-Marie" was taken a few days later by persuading native Tai to abandon the fight; some other Vietnamese and African troops deserted too.

During the next two weeks the Viet Minh tightened the noose around Dien Bien Phu and dug tunnels to approach the French inner positions.

The French commander on the scene, Christian de Castries, proved ineffective, but could not be replaced.

Supply from the air was difficult because of the the Vietnamese anti-air guns and the loss of Gabrielle prohibited the use of the airstrip.

Many supplies that were parachuted in ended up in the hands of the Viet Minh.

The start of the rain season at the end of March turned the valley into a quagmire and bogged down the tanks, which were already hampered by the thick vegetation.

At the end of March the Viet Minh launched large assaults on the remaining French positions.

These lasted a week and had mixed results because of tenacious French resistance.

Their artillery and one fighter-bomber attack proved vital in repulsing the attacks; the tanks could contribute little.

The Viet Minh suffered heavy casualties that combined with poor medical care caused morale to plummet.

General Giap was forced to settle down to a kind of trench warfare.

However the French had suffered too and their supplies ran low, so that they could not take advantage of the Vietnamese troubles.

In early May the Viet Minh, reinforced with fresh troops, resumed the assaults.

After a week they overran the remaining 6,000 defenders.

The French lost the battle because they chose a wrong position, vastly underestimated the resolve

and especially because of the superior supply system of the Viet Minh, which was well adapted to the rugged terrain.

They did not have enough troops at Dien Bien Phu to launch the offensives that Navarre envisioned and basically sat tight, waiting to be defeated.

At the large cost of 4,000 - 8,000 dead and 9,000 - 15,000 wounded soldiers the Viet Minh

had defeated 16,000 French troops, only about 6% of French strength in Vietnam, though including some of their best soldiers.

About 3/4 were taken prisoner.

Dien Bien Phu was not a decisive battle that turned the cause of the war,

but it did set the tone for the Geneva peace talks that were already underway in April,

giving the Viet Minh a strong bargaining position.

In the Geneva peace negotiations, Vietnam was temporarily divided in two halves, the north communist and the south under French rule until 1956 CE.

The division of the country lasted longer than intended and eventually led to the Vietnam War.

War Matrix - Battle of Dien Bien Phu

Cold War 1945 CE - 1991 CE, Battles and sieges